Anger in history - Part 2

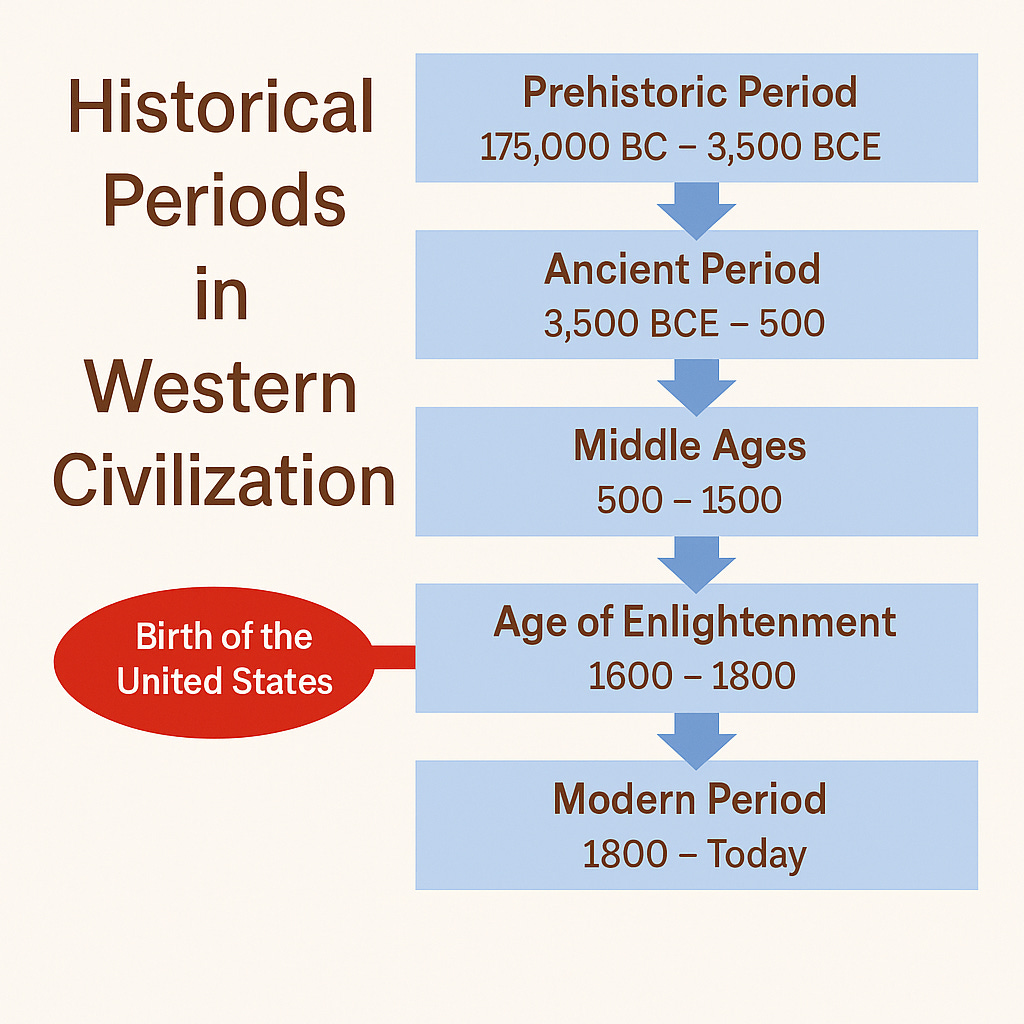

A psychohistorical interpretation of how anger expression has evolved over the ages, from prehistory to the early modern era.

Modes of anger expression in past eras

Continuing the discussion on the dynamics of anger in history, let’s delve into the past with a brief psychohistorical sketch of how modes of processing anger have changed over the centuries. History, one University of California history professor I remember saying, is always an “interplay between continuity and change.” For our inquiry, continuity can be considered our basic “human nature” or human psychology. Change is a process mediated by a myriad of cultural and social influences and filters through which this essentially biological substratum is expressed and manifested. 1

Prehistory (40,000 -?- to circa 6,000 BCE) 2

If we go back far enough in the human past, we can inquire into what life was like prior to recorded history, before there were any extent written texts or “documents.” The domain of prehistory, then, is one of far-reaching speculation based on very limited evidence.

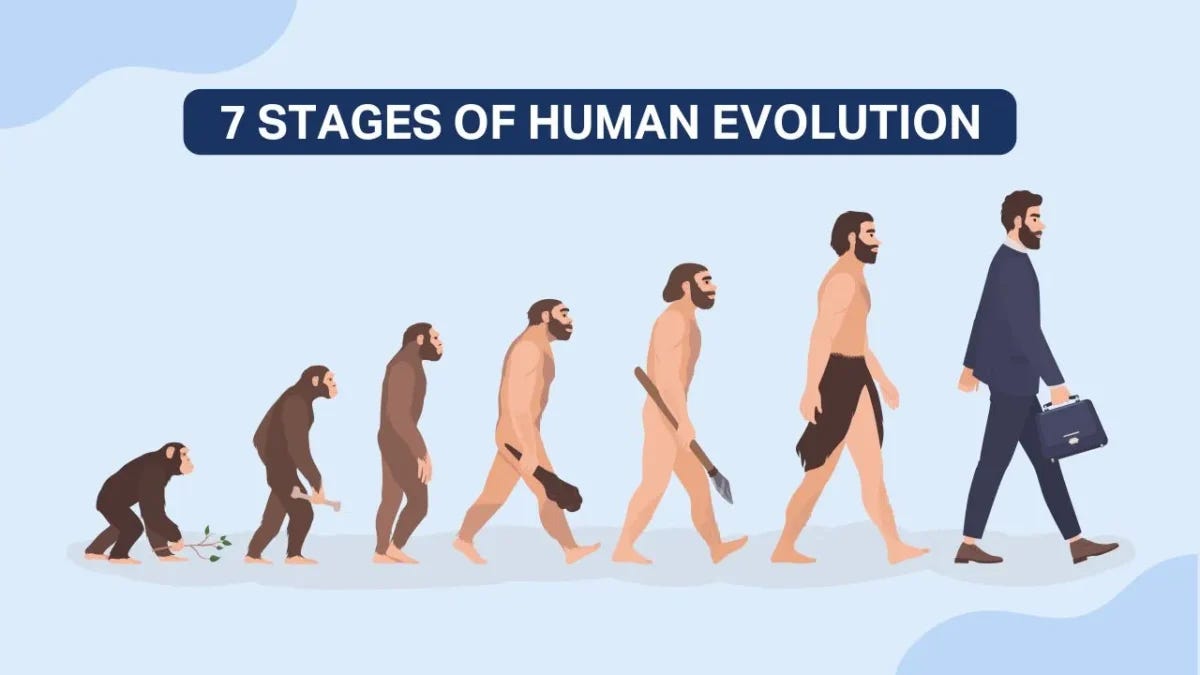

There are a fascinating array of thought-provoking books that examine prehistory, and I recommend if you haven’t read them, three “big history” works that are “good reads” and can shine a light on to our topic. None specifically discuss “anger in history” but they provide a useful framework for exploring it. The first isYuval Harari’s book Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2015.) In looking at what the evidence shows regarding the early evolution of humankind from our animal origins, Harari focuses on symbolization and the emergence of language. He argued that language allowed the invention of mythologies, “memes” and religious narratives that served as a means to unite larger populations that were no longer embedded in small face-to-face social groups. In human evolution, pre-history was marked by progress over time from primitive implements (the proverbial “Stone Age”) to weapons (sticks then spears) and then use of tools - but technology was not enough to make us human. We needed language - and symbolism. 2

With civilization (complex settlements beyond small hunter-gatherer groups) and the development of language, humankind then began to interact within and through culture, and start to seek to understand themselves and others. Written language and some form of books followed. And part of culture are the social customs and expectations regarding the expression and meaning of emotions or affect, including anger. With language, however, (see Wittgenstein for the philosophical dimension) came not only unity but the potential for division and verbal misunderstanding, and as we shall, the construction of ideology and ideologies that could then be dominated by either love or hate. 3

A second recommended reading is by the Harvard psychologist Stephen Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2011). As the title implies, Pinker agrees with the 1651 vision of Thomas Hobbes that life in the “state of nature” was “nasty, brutish and short.” Over the centuries, Pinker argues, humankind in the West was domesticated. One might say that culture brought about “anger management” (as in pre-school, “use words Johnny, don’t hit”) as language allowed communication and negotiation to replace and overcome overt and physical conflicts. Remember Freud‘s comment that the caveman who uttered the first curse instead of throwing a rock or a spear was taking a step forward toward civilization.

Over the centuries, Pinker argues, social organization and culture helped to bring about a decrease in violence, with angry disputes being constrained by having a legal system to resolve them. And by moral values which encouraged us toward being kinder and gentler. (Freud called this the “superego”) Many have disagreed with Pinker’s thesis and all we have to do is consider the very bloody European 20th century (and now with Russia attacking Ukraine in the early 21st) to disagree, but his argument does make sense in regard to individual violence. Supporting Pinker’s thesis, Norbert Elias in The Civilizing Process, (1939, republished in 1969 and 2012) make a sophisticated case in accord with Freud that civilization emerged gradually, and is an achievement both individually and collectively. Especially in the post-medieval world, Elias argues, Western culture successfully established standards in behavior regulating sex, violence, body functions, and manner of speech, to the point we came to have some agreement regarding what is considered “civilized,” refined and acceptable vs. what is coarse, boorish and unacceptable behavior. 4

This was a slow and uneven process and each historical age considered has been its own style regarding anger expression, and “anger management.”

Antiquity (cica 4000 BCE to 500 CE)

Michelangelo’s Moses

While anger is a human universal, it is expressed differently and given variegated meanings in different cultures and different ages. One look at the Code of Hammurabi in ancient Mesopotamia, with its attempt to both encode and regulate the primal moral instinct of “an Eye for an Eye,” and the Judaic stories of an angry Moses and the righteous slaughter of the Philistines, or Homer’s The Iliad, reinforces the generalization that this was, if not a “barbaric” era, one replete with rage-fueled aggression. The heroic warrior Achilles was so angry over the theft of his favorite captive woman that he could hardly be restrained. It can be said that Achilles' anger - the famous “Wrath of Achilles” is “the central driving force of the Iliad, shaping the entire plot and leading to immense suffering and death on both sides of the Trojan War.” 5

Roman civilization lasted almost as long as medieval, and Greek (Hellenic) culture carried over into most of the Roman period. Thus Edgar Allan Poe praised them equally in his phrase “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome.” These words subtly captured a difference, whereas Hellenic genius was in art, theatre and philosophy, Romans excelled in building - with grand engineering and in the building a great empire. Conquest and the gore of what took place in the Colosseum also embodied the shadow side of Roman “grandeur.”

(Some haunting music to accompany our arduous march through history.)

Rome inherited and continued the warrior culture and ethos of the Hellenic period. Virgil’s epic poem The Aeneid (19 BCE), for example, portrays the founding of the city of Rome and has as a major theme anger, its destructiveness, and its symbolic expressive meaning.

All 3 main protagonists, Aeneas, Dido, and Turnus struggle mightily to control their rage in differing and complex contexts with often transformative but tragic consequences. And the story begins with the fury of the goddess Juno:

The Aeneid begins with these famous lines:

I sing of arms and the man, who first from the coasts of Troy,

exiled by fate, came to Italy and the Lavinian shores,

tossed about much on land and on the deep by the power of the gods,

on account of the unforgettable anger of cruel Juno.”

Anger in the literature of Antiquity was most often llnked to a virtuous masculinity, destructive but inevitable. As a counterpoint, the Roman Stoics emphasized how to be calm and avoid out-of -control emotions, including, of course, those of anger.

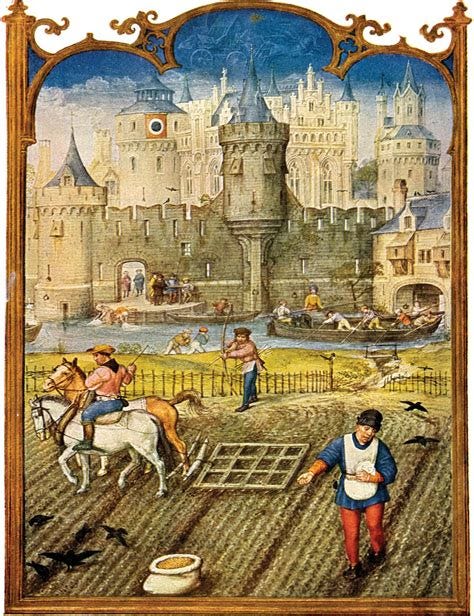

The Medieval Era (500-1500 BCE)

The Middle Ages in Europe lasted roughly 1000 years, and so it should not be a surprise that it is usually considered to have laid the institutional and cultural foundations of the Western modern era including the beginnings of universities, guilds, limited government, city-states, the nation-state and the idea of international law. 6

What were the patterns of anger expression that characterized this era?

Once again as with Antiquity, we know but little about what life was like for commoners. We can assume “human nature” was the same, people got angry in varied degrees and managed it as best they could. Chaucer's Canterbury Tales (circa 1389) “provides a rich tapestry of human emotions, and anger is depicted in various forms, from the deadly wrath of the rioters in The Pardoner's Taleto the petty indignation of the friar and the fiery marital disputes of the Wife of Bath. These portrayals offer keen insights into the psychological complexities of anger and its often-destructive consequences in medieval society, reflecting human nature's timeless struggle with controlling powerful passions.” 7

The medieval system was a class (and caste) society in which a small aristocracy (quite a small percentage of the population, estimated in Western Europe and Britain to be no more than 3-4%) dominated a mass of mostly impoverished peasants Alongside the nobility, the clergy had elite status, with an even smaller percentage the inhabitants of towns and very small cities. 8

The nobility was a warrior elite that had a monopoly over the means of violence, and rebellions by the peasantry were met with savage repression. Warfare tend to be small scale, stylized and targeted, rather than mass warfare, and personal conflicts amongst nobles were often settled by the custom of the duel.

Medieval society was a Christian culture permeated by pervasive religiosity, and a religious sensubility then shaped the style and symbolic meanings of anger expression. Roman Catholicism imposed a moralistic culture by which salvation was achieved by the avoidance of sin. Sex separated from reproduction (lust) was a major (Cardinal) sin, as were the other major excesses, e.g greed, envy, gluttony, sloth and -of course - anger or wrath.

St. Thomas Aquinas, the great systematizer of Medieval Catholic theology, had a lot to say about our most powerful and pesky (outside of lust) emotion. His views were nuanced, and exemplify what is the general Biblical especialy New Testament approach to angers, summed up in Paul’s words - “Be angry, but sin not.”

Aquinas, similar to the perspective I described in Part One discussing Neil Clark Warren’s views in Make Anger Make Anger Your Ally, did not see anger as intrinsically bad or evil. It becomes so only when it overwhelms reason.

“If anger is inordinate, it is a sin, either because the object is not deserving of anger, or because it exceeds the measure of justice” (Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 158, Art. 3).

The Catholic Church was complicit with and sometimes even encouraged the rapacious aggression and violence of the Crusades. This can also be interpreted as a feeble attempt to channel the aggressivity of monarchs and feudal warlords outwards externally onto the “other” - of course, those who happened to be “infidels” and occupied “the Holy Land.” The core moral teachings of the church historically insofar as they stemmed from those of Jesus the founder of the faith, sought to restrain war and violence. The Catholic doctrine of the “just war,” for example. sought to place limits on war and violence, making self-defense the only valid moral justification for collective violence. The weakness and mildness of Jesus shines through (dimly) in this particular passage from Aquinas:

“Meekness is a virtue that restrains the passion of anger, making man slow to anger unless it is necessary” (Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 136, Art. 2).

Renaissance and Early Modern Era

As a prelude to the early modern era, the Renaissance was a cultural transformation that began in Italy around 14th century and extended into the 16th century. migrating north to Germany and England. It reflected the sweeping economic, social and political change and upheaval of this period.

In Italy, the courtly elite strove to groom itself to stand apart from and above the unwashed masses. Castiglione advised: “The courtier should not be moved by anger or resentment, as those feelings are the bane of reason." (The Book of the Courtier, 1528.)

As Norbert Elias pointed out, part of historic class development was the cultural refinement of instinct, that included containment of anger, and in the medieval period, the feudal code of honor, and the cult of chivalry. The Renaissance was more about individuals managing their emotions (including anger) and putting them to use.

Farther to the north, fallowing the period of the impetuous Henry VIII and basking in the glow of Queen Elizabeth’s “Golden Age”, Shakespeare told his audience: “Heat not a furnace for your enemy so hot that it singes yourself.” (Henry VIII).

Machiavelli, sometimes called the originator of political science, counseled Renaissance rulers to manage their emotions carefully, and to use emotions to gain or keep power. In The Prince his realism seems to veer into cynicism, as he sought to coach the new Medici ruler of Florence to be strong and not flinch from taking harsh actions to ensure his political survival and the good of republics.

“Men are driven by two principal impulses, either by love or by fear,” he advised, and if a prince or monarch cannot get his subjects to love him, he must ruthlessly employ fear and intimidation. Such was the bloody rough and tumble of politics in northern Italy of his time, a reality he experienced first hand. “Machiavellian” has a definite pejorative meaning today, but he is best understood as someone who did not necessarily endorse “realpolitik” but sought to realistically describe its role in statecraft. His posthumously published Studies on Livy (1528) show that he was actually an admirer of the ideals of Roman republicanism and civil liberty.

Great literature and art reflects both social and especially cultural change. The 19th century Swiss historian Jacob Burkhardt in his acclaimed History of the Renaissance in Italy (1860) demonstrated that a major theme of Renaissance art is the “birth of the individual” emerging from the Medieval world, one in which the individual was defined by and submerged by their group identity.

In what has called the Northern Renaissance, in Elizabethan England, William Shakespeare (1564-1616) can be seen as an exemplar of this cultural change. In his exquisite sensitivity for human psychology, he was unprecedented in his capacity to portray the viccissitudes of emotions and their “management.” In Henry VIII and King Lear, he presented Kings in the throes of rage, and in Hamlet a Prince paralyzed by indecision and anxiety.

The Enlightenment (circa 1650 to 1800)

The Enlightenment was another cultural transformation, this time beginning in England and spreading throughout the western world. Sometimes called the Age of Reason, it begins in epistemology - how do we know what we know?- and in its later decades the end of the 18th century, especially explored moral psychology and analyzed the nature of political freedom and justice.

What did the great Enlightenment rationalists of the 17thcentury and moral philosophers of the 18th, have to say about anger?

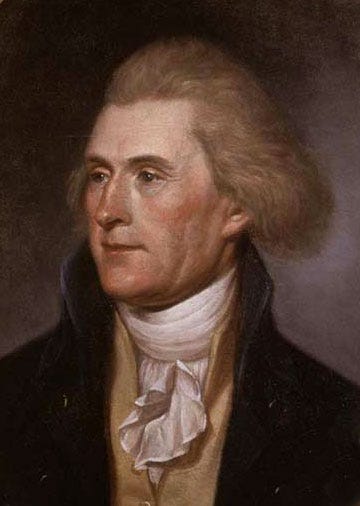

Descartes channeled the Stoic tradition in his non-epistemological writings with admonitions that while anger is a natural instinct, it must be carefully restrained using reason. Kant, more moralistically inclined, looked at passions and emotions with suspicion. He saw them as dangerous impediments to virtue, that required strenuous moral effort to overcome. The calm Thomas Jefferson is often said to have offered this pragmatic advice: “If you are angry, count to 10 before you speak. If you are very angry, count to 100, but it appears thar this was actually Mark Twain’s homespun counsel.

The European Enlightenment worked to bring about a kinder and gentler society, a more rational and humane approach to criminal justice, and government that respected due process and the human right to enjoy “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Jefferson and the rest of the founders of the American republic can be considered representatives of the American enlightenment, stepped in the classical heritage of western thought. The Enlightenment, and the America founders of our republic, embodied an ethos of reason and an attitude of measured moderation in the processing of anger expression.

With the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution reached a high point. By the 1800, its principles inspired a democratic revolution and sparked an Industrial Revolution that would begin to transform the globe and construct the modern world in which we live - one which Karx Marx and Frederick Engels described in 1848 in these words:

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

Modernity unfolded over the 19th and 20th centuries and brought progress but also conflict, hope and dread, trauma and anxiety, and often was marked like all past eras - by anger.

In a concluding Part 3 of this psychohistorically-informed essay on the role of anger in history, we will finish our cultural interpretation of its varied modes of expression in the modern, then post-modern age. Part 3 will also end with a discussion of modern social and political movements and leaders who exemplify how anger collectively can bring either destruction and hatred - or beneficial and constructive change.

____

Notes

1. The dialectic between continuity and change pertains to our subject in a way similar to the nature/nurture debate. Nature does not define and completely determine the fate of humankind, but rather shapes and provides the context and environment in which its development emerges.

See especially Ernst Cassirer, The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms, and the works of Suzanne K. Langer, including Philosophy in a New Key (1942.)

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (1953.)

Norbert Elias’s The Civilizing Process (1939) was published 8 years after Freud’s speculative but brilliant Civilization and Its Discontents (1930) and carries forward its central thesis that civilization is built upon centuries of the repression of instinct.

This is the apt interpretation of Chaucer’s tales by ChatGPT.

A good analysis is Jacques Le Goff, Medieval Civilization: 400 - 1500 (1992)

Again, an observation from my ChatGPT savant AI bot that was too good to not quote.

For a comprehensive survey that covers many of these themes, I recommend Jackson Spielvogel, Western Civilization (12th edition, 2025.)

For a popular, non-academic well-written book on the Medieval Irish contribution to civilzation and modernity, see Thomas Cahill, How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland's Heroic Role From the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe, 1996.

For an analysis of the real Machiavelli beneath the stereotype, see Michael Unger, Machiavelli: A Biography, 2012.

On the author of the Declaration of Independence, see Fawn Brody, Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (1974.) Brody’s pioneering psychobiography, which showed that he had a 30 year long intimate relationship with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, was met by rejection and scorn by traditional historians who preferred a hagiographic approach to their revered subject. Decades later, her once controversial thesis was confirmed by DNA evidence.

This is fabulous! Thank you so much! I am actually listening to the audio book of Sapiens now.