Anger in History , Part 3

Reflections on the psychohistorical dimension of anger expression in the West in the modern era, with a perspective on angry leaders and anger-driven social-political movements

In the first two parts of this what will now be four part series, we looked at the psychology of anger, how anger can be managed or mismanaged, and how important it is to understand the affect of a anger both on an individual level and collectively. We also examined how the expression and cultural forms of anger have changed over the ages, from prehistory up to the beginning of the modern era. Anger is part of human nature and psychology, but in each historical time period the raw energy of anger is culturally expressed or channeled in varied ways. This interpretation of anger in history from 1800 to the present covers an enormous time span, so it will necessarily only be a surface level sketch serving as an introduction to some final more in-depth conclusions about the subject.

It is of course arbitrary, but one can say that the “Modern era” began around 1800, as two developments that had begun in the West by the 18th century continued to unfold.

1) The first development was the triumph and acceleration of the scientific revolution, combined with its technological applications in the 19th century. In what has been called the Industial Revolution the capitalist system was joined to technology to transform manufacturing, agriculture and commerce, to bring about by the end of the century the beginnings of an urban and secular society.

(This classic Charlie Chaplin film, which provides a comedic, but profound look at life in the industrial age, is well worth watching.)

2) The second major development was the gradual replacement of what is called in European historiography, the “Ancien regime,” the Medieval hierarchical corporative social order of nobles and peasants, supplanted gradually by what can be called a class society, in which a rising middle class co-existed uneasily with an emerging industrial working class.

3) The third development was cultural and ideological. Middle class culture and norms overtook the aristocratic ethos (think “chivalry” and “noblesse oblige”) and modern secular ideologies proliferated and flourished. These ideologies in the 19th century included liberalism (stemming from the Enlightenment ideas and ideals, conservativism, socialism, and nationalism. (See my Substack article, “Ideology and the Psychology of PoliticalExtremism,” 2025, for an analysis of this.) The 19th century, which has been also called the “Age of Ideology “ brought the triumph of science, and at the same time, a crisis of meaning. As “mechanization took command “ the question arose: what would become of enduring, traditional values rooted in religion and tradition? An important aspect of this cultural intellectual transformation was the contest between religious orthodoxy and modern secular, scientific attitudes, and a sense of intellectual and spiritual crisis.

So where does anger fit into these historical developments which continued through the 19th and into the 20th century?

Human beings having their innate biological nature, anger was obviously a constant of everyday life, an emotional force to be managed by both rich and poor, the powerful and the powerless. But the cultural forms of anger expression differered significantly, depending on what social class you were in. The upper classes as we have seen, tended to emphasize self control of unruly emotions. The commoners, on the other hand, were known by the elites for being unruly and more uninhibited. Fear of their aggression led to them being considered “the dangerous classes,” prone to crime and violence.

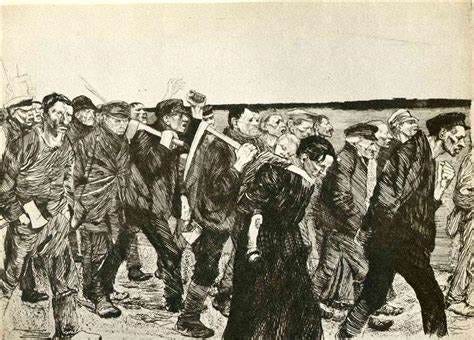

A prominent theme during the first half of the 19th century, was the growing protest of the downtrodden against the dislocation and impoverishment caused by rapidly advancing industrialization. In France especially, workers rose up in 1815 and 1830 and in 1848 to defend their rights. Silesian weavers in Prussia displaced by machines, took to the streets with violence in 1844, inspiring the young philosophy graduate, Karl Marx. Anger at social injustice was often portrayed in 19th century art and literature.

The novel Les Missrables by Victor Hugo (1862) expressed this theme powefully (and recently irony was broken. a critic noted, when Trump‘s millionaire entourage celebrated its theatric performance at the Lincoln Center.

“Do you hear the people sing?

Singing a song of angry men?

It is the music of a people

Who will not be slaves again!”

This trend of workers fighting back in angry revolt on behalf of themselves and for liberal reform was also captured in 19th century painting.

Delacroix’s “Liberty Leading the People” (1830)

After mid-century, working class anger in the personal realm continued to be managed as it had before, but the onslaught of capitalist transformation led to workers forming labor association or unions, then labor political parties to protect and pursue their interests. The anger fueling workers social protest often still did break out in violence. Emile Zola portrayed this quite powerfully in his novel Germinal (1885) a searing portrayal of the brutal conditions faced by coal miners in northern France during the 1860s, though it resonates strongly with the social unrest of the 1880s as well. The novel is widely regarded as Zola's masterpiece and a cornerstone of social realism.

Here are a few powerful lines that capture the miners' fury and desperation:

"Men were springing forth, a black avenging army, germinating slowly in the furrows, growing towards the harvests of the next century, and their germination would soon overturn the earth." — Final lines of the novel

This metaphor of an "avenging army" rising from the soil evokes the inevitability of revolution.

Middle class culture, especially that of Victorian England, on the other hand was characterized by the prevalence of of decorum and inhibition of expression of emotions. Needless to say, except for some middle class idealists such as Dickens, Marx or Balzac, it also did not involve much concern for the plight of the workers.

In the writings of Sigmund Freud these cultural tendencies and psychic dynamics are extensively analyzed. Psychoanslyis, one can say, was invented to probe the hidden recesses of unconscious conflict amongst the middle class - rooted in Freud’s view, in the repression of instinct.

Anger, Masculinity, and Repressed Instinct: 1880–1930

Known as the “Victorian era,” the later 19th century was marked, especially among the bourgeois classes, by a suppression of instinct, emotion, and sexual desire under the veneer of moral rectitude and restraint. In this cultural ideal, Victorian men placed women “on a pedestal,” while keeping them subordinate—frequently indulging, behind closed doors, in a vast sexual underground of prostitution and taboo-breaking vice. A culture that denied the body in public often indulged it in secret.

By the 1880s, Sigmund Freud had begun his explorations into the unconscious dynamics of the authoritarian nuclear family—its hidden traumas, repressed drives, and hypocritical demands. He would later frame civilization itself as a trade-off: a relinquishing of instinctual freedom in exchange for security and order. In Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), Freud wrote:

“Civilized man has exchanged a portion of his possibilities of happiness for a portion of security.”

And elsewhere:

“The liberty of the individual is no gift of civilization. It was greatest before there was any civilization.”

This foundational tension—between the individual’s instinctual drives (including sexuality and aggression) and the internalized rules of the cultural superego—created a kind of psychological pressure cooker. Anger became not just an emotion but a latent force waiting for release.

By the turn of the century, this pressure began to find explosive and often indirectexpression. In the cultural mood of Europe and America, especially among men, there arose a fear of emasculation and feminization. Middle- and upper-class men felt their instinctual energies—especially aggression and righteous anger—being dulled by modern comforts, domesticity, and moral restraint.

Few captured this mood more prophetically than Friedrich Nietzsche, who urged that we do “philosophy with a hammer” to shatter the idols of conventional morality. In On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), he diagnosed the moral worldview of the West as shaped by ressentiment, a repressed and twisted anger of the weak:

“The man of ressentiment is not upright and naïve, nor honest and straightforward with himself. His soul squints.”

Nietzsche’s “will to power” was not simply about domination—it was a call to affirm life, instinct, and force in the face of what he saw as a “life-denying” Christian and bourgeois morality.

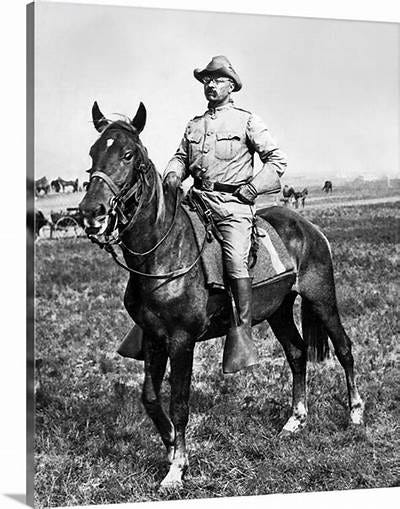

Across the Atlantic, Teddy Roosevelt gave this yearning for unleashed masculinity a distinctly American expression. In his 1899 speech The Strenuous Life, Roosevelt preached against ease and softness:

“I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life… the life of toil and effort, of labor and strife.”

For Roosevelt and other elite men, imperial adventure and military conquest offered a kind of moral and psychological remedy to the supposed sapping of masculine energy by civilization. He warned against a society growing too soft, too “feminized”:

“The weakling and the coward are out of place in a strong and free community.”

It is no coincidence that Roosevelt’s most ardent calls for war, discipline, and empire occurred during a period of American imperialist expansion, and when gender roles were being contested, industrial society was domesticating many men’s work, and women’s suffrage was gaining momentum.

Imperialism, then, was not merely geopolitical. It was also psychic—an outlet for collective male aggression, rage, and the reassertion of dominance.

In Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), we find a dark literary mirror of this mood. The novella exposes the psychological decomposition of men who, when freed from the restraints of civilization, confront their own primal instincts. Of the European colonial project, Conrad writes:

“The conquest of the earth… is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much.”

Kurtz, the story’s tragic figure, becomes the personification of repressed rage turned inward and outward, his final utterance an indictment of both empire and human nature:

“The horror! The horror!”

Ernest Hemingway, writing in the wake of World War I, offered yet another variation on masculinist anger—this time quieter, more internalized. His prose was minimalist, stripped down, like the men he wrote about: wounded, stoic, emotionally silenced. In The Sun Also Rises (1926), he writes:

“You can’t get away from yourself by moving from one place to another.”

And in A Farewell to Arms (1929):

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

But Hemingway’s world is one where brokenness is rarely processed through vulnerability—instead, it curdles into muted despair, alcoholism, violence, and what we now might recognize as PTSD.

The Silencing—and Awakening—of Female Anger

While male anger in this period often found sublimated release through war, empire, or literature, female anger—no less real—was typically dismissed, pathologized, or turned inward. In Victorian society, a woman expressing rage was often labeled “hysterical,” “unwomanly,” or mentally ill. The ideal woman was passive, moral, self-sacrificing—trained to manage her emotions but never to assert them.

Whereas Freud explored male neurosis as a product of instinctual repression, his female patients—often diagnosed with “hysteria”—presented another side of the same cultural coin. Their symptoms (paralysis, anxiety, dissociation) can be read as expressions of repressed trauma and anger, trapped within a cultural framework that denied them voice and agency. These women often could not express their rage at patriarchal control, sexual violence, or their social subordination—so it appeared through the body instead of language.

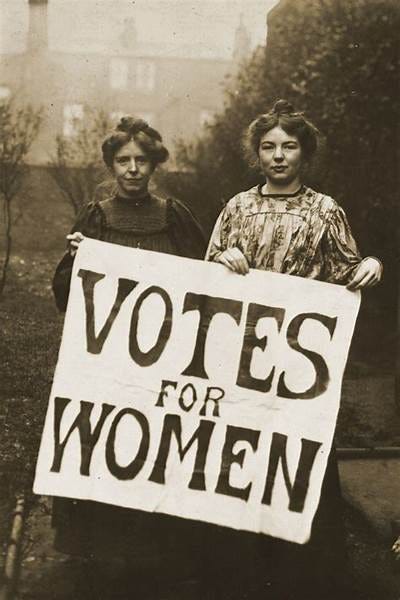

Yet the fin-de-siècle (end of the century) also saw the beginnings of a collective awakening. The Suffragette movement, emerging in Britain and the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was in many ways an eruption of suppressed feminine energy. What had been silenced was now shouted in the streets.

Militant suffragettes like Emmeline Pankhurst did not shy away from anger. In fact, they reclaimed it:

“We are here, not because we are law-breakers; we are here in our efforts to become law-makers.”The use of hunger strikes, public protests, and even property destruction by some factions of the movement expressed a deep-seated frustration at being excluded from political life. These acts were, psychohistorically speaking, expressions of a long-repressed collective fury.

Emmiline Pankhurst, militant suffragette

Just as male writers and politicians were dramatizing the perils of feminization, women were transforming anger into a demand for dignity and democratic voice. What Freud saw in the individual psyche—repressed instinct pushing for return—was mirrored in society itself. The feminist anger of the early 20th century was not irrational; it was a message that women’s equality was long overdue.

This period—spanning Freud’s early work, Nietzsche’s late writing, Roosevelt’s jingoism, the colonial unravelings of Conrad, the wounded stoicism of Hemingway, and the rising defiance of the suffragettes—offers a psychohistorical map of suppressed anger. In the name of “civilization,” instinct was denied; in the name of masculinity, it was reasserted—often violently. In the case of women, that anger was silenced until it broke through the barriers of culture and custom, demanding recognition.

The costs of this psychic economy would erupt fully in the twentieth century’s wars, revolutions, and emancipatory movements. As Freud warned, repression does not abolish instinct—it only ensures its return, “with interest.”

Time and space do not permit a discussion here of the horrific world wars of the first half of the 20th century and the rise of fascism and totalitarianism. We will now fast-forward to the post-1945 era to bring this brief exploration of the cultural expressions of anger in the modern period to a close.

Post-1945: The Shifting Tides of Anger in American Culture

In the aftermath of World War II, the 1950s in the United States were marked by a dominant ethos of calm, conformity, and containment. The “white picket fence” era, epitomized by TV shows like Ozzie and Harriet, promoted a vision of the content, nuclear family in a booming middle class. Emotions, especially negative ones like anger, were largely repressed or rendered invisible. Women’s anger was especially taboo, tucked behind smiles and aprons. One could ask: did Harriet ever get angry — or was anger itself domesticated, hidden behind suburban curtains?

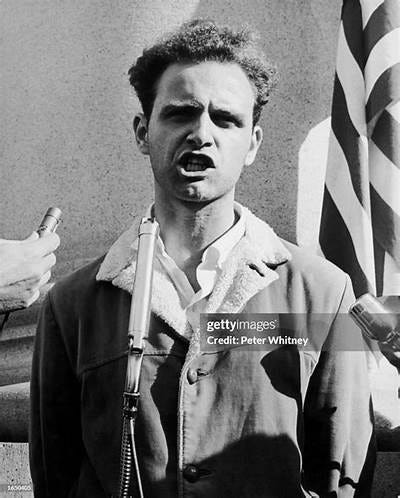

By the 1960s, this placid facade began to crack. Youth-led protest movements, galvanized by civil rights, antiwar fervor, and a desire for liberation, brought anger to the forefront of public expression. Mario Savio’s fiery speech on the steps of Sproul Hall at Berkeley in 1964 captured a generational revolt: “There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious…” he declared, urging resistance. The decade became a cauldron of moral outrage, rebellion, and upheaval — against racism, imperialism, sexual repression, and the bureaucratic state. Anger was no longer hidden; it was raw, collective, and sometimes incendiary.

Mario Savio, UC Berkeley, 1964

The 1970s carried forward this rebellious energy but also showed signs of disillusionment. The decade saw the evolution — and in some cases the dissolution — of 60s idealism. Cultural anger turned more inward and fragmented: disillusionment with the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, and the collapse of utopian dreams brought cynicism and fatigue. Sidney Lumet’s 1976 film Network captured the spirit of this decade in the character of Howard Beale, who famously shouted: “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!” It was a populist howl — a mass media-age rage against alienation, economic uncertainty, and powerlessness.

By the 1980s, American anger underwent another transformation. While Reagan-era optimism and consumerism glossed over deeper discontents, anger didn’t disappear — it went underground, privatized, or was managed. The emergence of “anger management” programs (popularized culturally by the 2003 film “Anger Management,”) signaled that rage had become a clinical issue, something to be treated rather than expressed. But beneath this attempt at emotional control, resentments simmered — especially among those left behind by the new economy.

In the 1990s, anger erupted in more tragic and violent ways. The rise of school shootings — most infamously, the Columbine massacre in 1999 — pointed to a new form of alienated, often nihilistic rage. This was a privatized, deadly anger often linked to young men, bullying, and the perceived injustices of a hyper-competitive, emotionally isolated culture. The language of anger became increasingly saturated with firearms and despair.

Video footage of the 1991Columbine high school shooting massacre

From 2000 to 2016, anger took on an increasingly political and populist tone. Globalization and deindustrialization hollowed out working-class communities, while the 2008 financial collapse deepened economic insecurity and distrust of elites. Movements like the Tea Party channeled right-wing anger into anti-government protest, while Occupy Wall Street voiced leftist rage at economic inequality. But it was Donald Trump who proved most adept at turning cultural resentment into political power. His 2016 campaign gave expression to simmering frustrations — with immigration, global trade, racial change, and perceived liberal condescension. Trump didn’t manage anger; he stoked it, performing it, embodying it.

By the 2010s, American politics and culture were defined by polarization, grievance, and a near-constant sense of outrage. With the internet spreading embers, social media poured gasoline on every emotional spark, rewarding fury with attention and clicks. Anger, fueled by talk radio, became both content and currency for high ratings. Whether from the left or right, it was no longer just a personal emotion — it was a shared political identity. And increasingly, it targeted the “other,” eroding empathy and fueling tribalism.

Two Angry Leaders a Century Apart: Adolf Hitler and Donald Trump

To conclude this discussion of anger and history, let’s take a look at 2 leaders, both of them having as a prominent feature of their leadership the projection of anger and resentment.

Adolf Hitler, one of the most destructive leaders in modern history, was born in Austria in 1889, the son of an authoritarian Austrian civil servant. His mother was much younger than Adolfs father and previously had been a maid in his household. Young Adolf was emotionally and physically abused by his domineering father, and coddled by an indulgent mother who allowed to drop out of high school at 16, after his father died when the boy was 13.

Ironically, given his later career as a swaggering militarist, Adolf was as a boy and teenager, sensitive, artistically inclined, and enamored of Wagnerian music and art. As an undisciplined teenager, he was described by a boyhood friend as having been a dreamer, but one who was also quarrelsome and peevish. Even while in school, he began to show a great interest in German nationalism.

After his mother died when he was 18, with his inheritance, young Adolf went to Austria in search of a career in art or architecture. The Academy of Art in Vienna rejected his application due to his only modest artistic talents and of his not having finished high school. He also absorbed the rampant antisemitism that flourished in Vienna from the 1890s to 1914, Adolf channelled his anger at being rejected by the Academy to resentment at those he said were responsible - “the Jews.” He got by with doing odd labor jobs, and by painting of small postcards. In 1912, to avoid the draft, he moved to Munich, continuing his amateur painting and, in August of 1914, with his life essentially going nowhere, he happily volunteered to join the German military to fight in World War I.

Hitler’s military career consisted of being a messenger on the front lines, rising no higher in rank than being a corporal. He was injured in a British mustard-gas attack in the fall of 1918, and was recovering in hospital outside Munich when he heard the news of the German high command’s surrender to the Allies in November 1918. He was shocked and reacted with resentment and rage. He quickly embraced the belief that Germany had not lost the war, but been betrayed by traitors at home.

His first job after demobilization was with the army as a political operative, spying on the many small political organizations that emerged in the wake of the collapse of the Kaiser regime. Part of this work was attending a meeting of a very small group called the German Workers’ Party, which promoted reactionary ultranationalist views laced with anti-Semitism. Their goal was to weld fascist nationalism to a pro-socialist workers’ program. “Nazi” of course means national socialist, previously an oxymoron, as the German Social Democrats had prior to World War One for decades strongly opposed war and espoused internationalism.

It was in the large beer halls of Munich in 1919 and 1920 that Hitler gained his fame, with his signature rageful speeches decrying what he called the traitors and alien Jews that had stabbed Germany in the back. His oratorical voice was shouting, shrill, filled with hate - and intensely angry.

As a demagogue, Hitler tapped into the resentment, frustration and anger of many Germans who despised the discredited status- quo and yearned for a champion “who alone could fix” Germany’s many problems. As a leader he tapped into their anger and exploited and magnified it, but in a way that did not resolve their problems but ultimately made them worse. We can see this as analogous to individuals who fail in successfully managing their anger and instead “explode” and project hatred outward. This kind of leadership provides a false cure, a “poison pill” that is framed by propaganda and promoted as a great remedy.

Donald Trump is our second example of an angry leader. This is not to equate Trump with Hitler, nor MAGA ideology with National Socialism. There are several obvious major differences. They are comparable in many respects, but not equivalent.

What they do have in common, in addition to ultra-nationalism and contempt for liberalism. is the centrality of the emotion of anger, coupled with resentment, disdain and contempt for their political enemies, and rivals.

So many of Trump’s speeches have anger at their core with a corresponding thirst for revenge and a desire for retribution.

Trump, born in Queens New York in 1946, grew up in a family system headed by a domineering, emotionally abusive father. His mother was, biographers agree, often not “present” for her son and was generally not someone who could be an emotional counterweight to the very controlling Donald Sr. Mary Trump, his granddaughter, and Trump‘s niece, has compellingly portrayed in her writings how tyrannical the old man could be, and how Donald stepped into his father’s shoes.

Psychoanalyst and psychohistoran Jeffrey Rubin points out thar of the traumas Trump experienced,

“One of the subtle but significant horrors was his father repeatedly telling him he is a “killer” and a “king,” which taught Trump to think he was the center of the world and that he must annihilate anyone in his way. In defining who he is and what he should be, his father hijacked and robbed him of his own authentic life. It is not surprising that Trump was terrified of being an abject “loser”—the phrase his family used at the dinner table when he was growing up to mock everyone. And it is predictable, if heart-breaking, that he pathologically accommodated to his father’s vision of him in order to keep alive the hope that the love that was absent from his parents might one day be forthcoming.”

Trump’s unprocessed and unmourned trauma created a person who is “at war with the world in a desperate and tragic attempt to avoid retraumatization.“

Unknowingly trapped in his own emotional void, Trump wields anger as his sword of retribution and revenge. The suppressed and submerged rage of his disgruntled. followers then is channeled into a leadership style of belligerence and intimidation. We are now in 2025 experiencing the consequences of this leadership style and Trump‘s unprocessed trauma.

In a coming final Part 4 of this series of articles on the psychohistorical aspects of anger in history, we will further explore how anger collectively can be channeled - or shall we say “managed - in another, a constructive way. As has been foreshadowed in this article in our consideration of the struggle for workers and women’s rights, there have been some leaders and movements in history that been able to an achieve the “alchemy” of transmuting frustration and anger into positive social and political change and transformation.

Anderson, Judith & Zinsser, Judith, A History of Their Own: Women in Europe, From Prehistory to the Present. Vol. II. 1988

Arendt, Hannah. The Origins . 1951.Bullock, Alan. Hitler: A Study in Tyranny. 1952 (rev. ed. 1962).

Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. 2002 .

Evans, Richard J. The Third Reich in Power. 2005

Frank, Justin A. Trump on the Couch: Inside the Mind of the President. 2018.

Gay, Peter. Freud: A Life for Our Time. 1988.

Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. 1987.

Hobsbawm, Eric. The Age of Revolution, 1789–1848. 1962.

Hobsbawm, Eric. Industry and Empire: From 1750 to the Present Day. 1969.

Marcus, Stepen. The Other Victorians. 1966.

Milburn, Michael & Conrad, Sheree. Raised to Rage: The Politics of Anger and the Roots of Authoritarianism. 2016.

Rasmussen, Kenneth. “The Trump Card: Demagoguery and Conspiracy Thinking in Psychohistorical Perspective.” Clio’s Psyche, 2016.

Rubin, Jeffrey. “False Cures.” (Paper to be presented at the 17th annual conference of the International Association for Psychoanalytical Self Psychology. (2025)

Stolorow, Robert. World, Affectivity and Trauna (2011)

Tavris, Carol. Anger: The Misunderstood Emotion. 1983 (rev. ed. 1989).

Trump, Mary. Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man. 2020.

Waite, Robert G. Hitler; The Psychopathic God. 1977 (republished1991.)

In response to a question (that now seems to have been deleted) which if I recall pertained to my describing people as hate-filled extremists those who are fully immersed in the MAGA ideology, or in any authoritarian rage based creed (it could also be extremist left-wing ideology like many versions of Marxism-Leninism,) thinking is hijacked by ideology, and self reflection falls by the wayside. I recommend you read Eric Hoffer’s book The True Believer. The toxic ideology actually allows the rage to be embraced, and there is no room for reflection or self correction. Of course, many political extremists do come later to reflect and modify their views, in retrospect. In

The author's work on the psychology of Donald Trump is both timely and essential, offering a powerful and accessible psychoanalytic framework for understanding the rise of modern authoritarian rule. By focusing on the interplay of splitting and projective identification, the article goes beyond simple political commentary to expose the deeper psychological dynamics that can destabilize societies and erode democratic norms. The detailed examination of Donald Trump’s background is particularly significant, demonstrating how unconscious processes can have real-world—and frequently dangerous—consequences, tracing their origins back to his early life. The author's insightful connection between his emotionally unavailable father and the formation of his defensive mechanisms provides a compelling lens for understanding his need to project his innermost insecurities onto others. This is a significant contribution to the study of Donald Trump today and a must-read for anyone seeking to understand the psychological underpinnings of our current political era. The article’s historical perspective, using Trumpian authoritarianism as a benchmark for other leaders, is a compelling and urgent analysis of a worldwide trend.